I’ve written before about using AI tools for various tasks, and I’ve been pretty clear that they still need human supervision for anything factual. But I’ve been experimenting with something that feels genuinely useful: an AI assistant that can actually do useful things on my behalf, not just answer questions.

I’ve been using Claude as an AI tool for a while. It was sort of the gateway drug for me; its writing and reasoning skills have been a better fit for my needs than any of its competitors. Then I started experimenting with Claude Code, the Claude-based AI coding tool, and have lately been using Claude Cowork (both of these will be the topic of future posts). But all of these tools basically work by executing specific instructions you give.

The assistant tool I wanted to try is now called OpenClaw. It was Clawdbot, but Anthropic didn’t like that intrusion on their trademark. Then the creator picked the (dumb) name “Moltbot,” but realized it was dumb and changed it again.

Whatever you call it, the basic idea is simple: an open-source project that runs on your own hardware and connects to your choice of messaging apps. I have it set up on a Mac mini in my office, and I talk to it through WhatsApp. Intstead of only the AI being a chatbot you visit in a browser, it’s more like having an assistant sitting at a computer 24/7, waiting for instructions. The assistant can do things on a schedule or on demand, and its capabilities are limited mostly by how willing you are to give it access to stuff.

I set it up on a Saturday afternoon; t only took about 30 minutes to set up OpenClaw on my Mac mini. I started by telling it to create skills to read and send email and calendar messages in Microsoft 365, then connected it to my robichaux.net mail account. I fooled around a little by asking it to do various cleanup tasks in my mailbox and my reminders app, all of which it did well.

A winter escape attempt

The next morning, I had a flight planned KHSV-KTLH to take Cecelia to visit Florida State‘s campus. The weather was forecast to be awful (remember the big winter storm in late January 2026? Yep, that was the weekend), with low ceilings, potential icing, and en route IMC pretty much non-stop. I used my normal combination of EzWxBrief, Foreflight, and skew-T diagrams to check the weather, and decided that we should leave Huntsville about 10. At that time, it was raining, about 40º at ground level, with a 3500′ ceiling. There was a line of moderate precipitation diagonally across our path for about 45 nm, but there was no forecast icing and the freezing level wasn’t a problem, so off we went. After a normal takeoff and climb out to our planned altitude, we bumped along through periods of showers until, sure enough, things smoothed out about 50 nm along. Then I had some time to think.

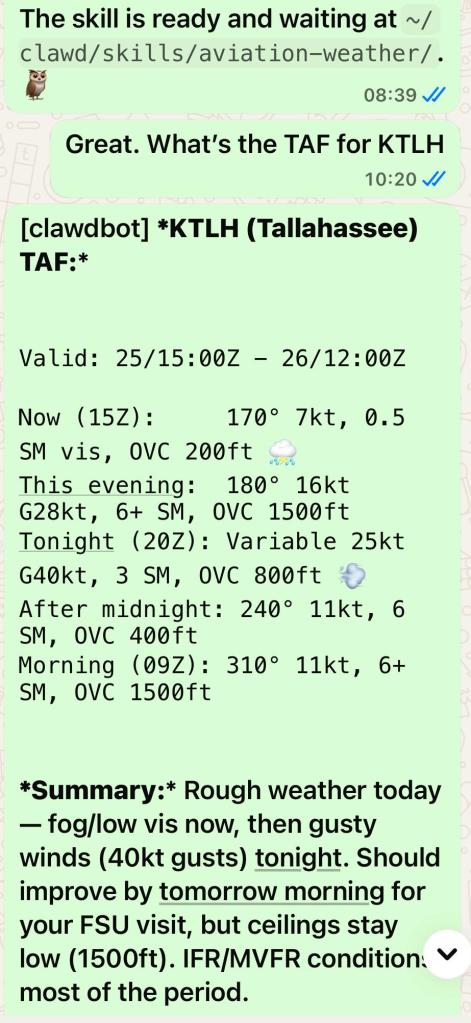

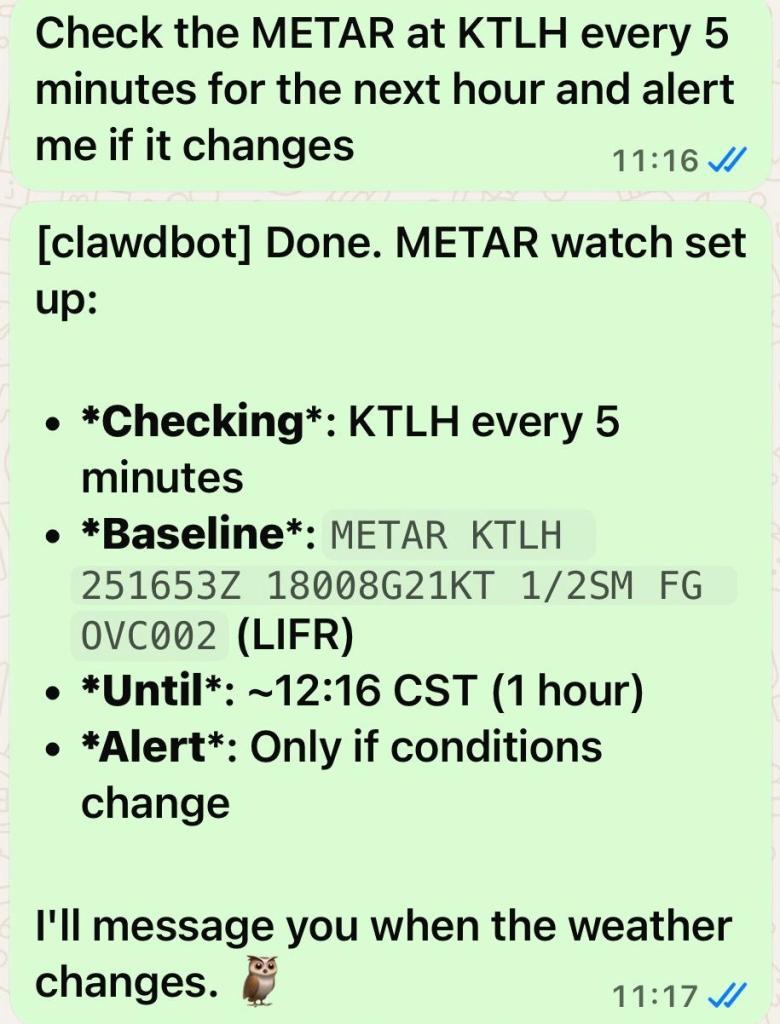

See, the current conditions at Tallahassee were 200′ ceilings. They were forecast to improve to at least 600′, and I’d filed Valdosta as an alternate, but I wanted to keep a really close eye on on the conditions as I went. That got me thinking about my helpful assistant.

Teaching old bots new tricks

Claude, Claude Code, Moltbot, and many other tools can be extended with “skills.” Skills are basically plugins that give the AI new capabilities. Some skills come built-in, and others you can create yourself—or, more interestingly, you can ask the AI to create them for you. A skill is essentially a self-contained module that extends what the AI can do. Skills can include code, configuration, and documentation. The AI can read the skill’s instructions and use it appropriately. Think of it like teaching someone a new procedure—once they learn it, they can apply it whenever it’s relevant. The important bit is that skills persist across conversations, so the AI “remembers” how to do things you’ve taught it.

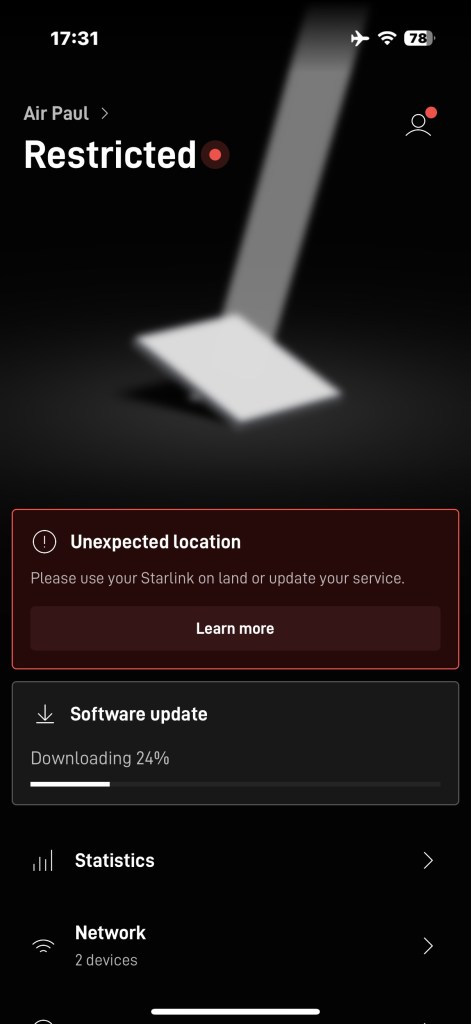

Now, luckily my plane is well-equipped. I have onboard ADS-B datalink weather, where the FAA uplinks ground weather data that can be displayed on my cockpit displays and iPad. I also have Starlink, so I can see pretty much every kind of weather data available on the Internet. But, well, I wanted more. I wanted my new bot to do some of the work and check the conditions to tell me if and when they changed, and for that, I’d need a skill.

I started simply by asking “Do you have a source for aviation weather data?” It didn’t—but instead of just saying “no,” it went looking. It found the NOAA Aviation Weather Center APIs (https://aviationweather.gov/data/api/), which provide access to METARs, TAFs, PIREPs, AIRMETs, SIGMETs, and all the other alphabet soup that pilots live by. Then it offered to create a skill to access those APIs. I said sure, go ahead. A few minutes later, I had a working skill that could fetch current weather for any airport.

Now, this may not seem earth-shattering. After all, in the plane I have the same data available from the ADS-B datalink and via the Starlink connection and (when in range) via VHF radio. And the skill itself is dirt-simple; it’s a small Python script that hits an open REST API. The point wasn’t to get the data to me, it was to get it to the bot so it could do stuff with it.

Armed with this skill, I could ask the bot to alert me if something changed. This is a valuable trick, since it meant I could carry on flying and let the bot tell me if anything interesting happened with the weather.

I set that alert when I was about 1:15 away. It ran for a while and… nothing changed.

Adding leverage to the skill

When I didn’t get any alerts, it was easy to confirm on ADS-B that the weather hadn’t changed. That was good, in that it meant the alert mechanism hadn’t failed, but it was bad in that I wouldn’t be able to land at Tallahassee. However, the fact that the bot’s based on a really powerful LLM started to come in handy right about now.

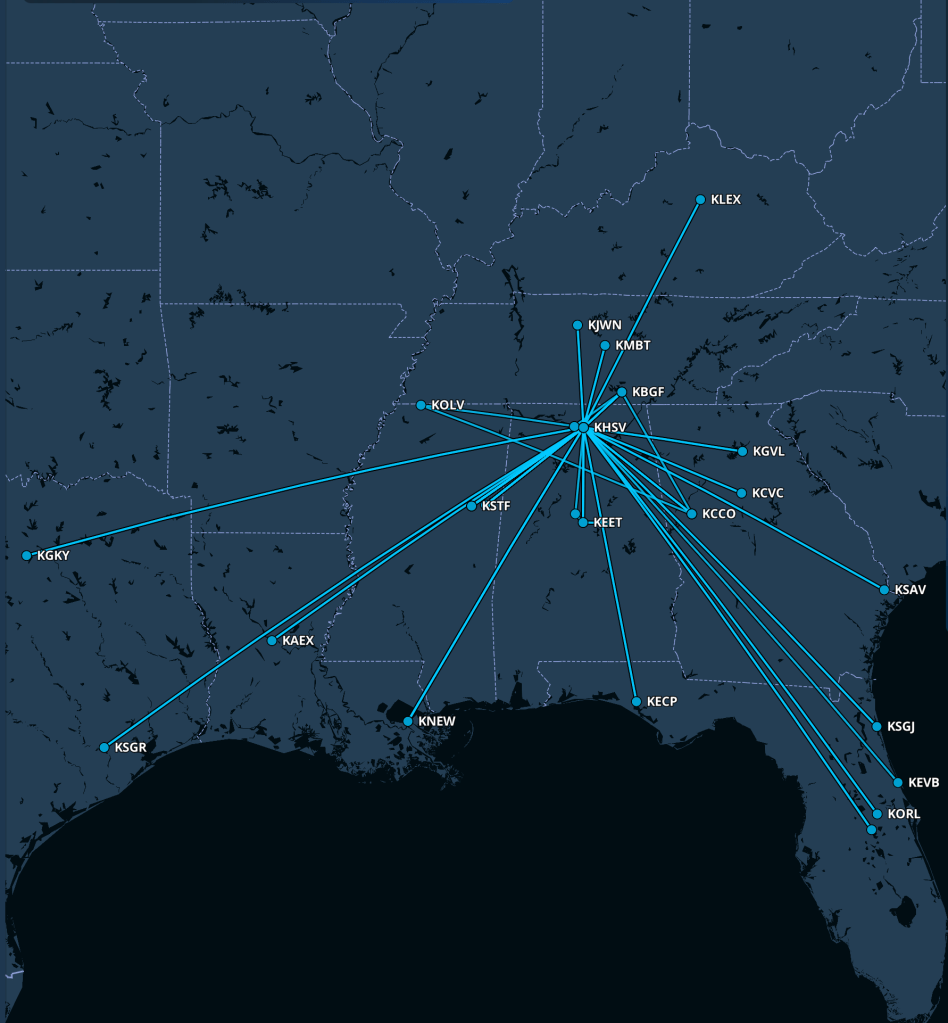

This simple query did several things that I didn’t explicitly ask for. It searched for airports, sure, and tried to figure out which ones had rental cars, but it also looked up the weather at each one and summarized it so I know that Panama City, Gainesville, and Jacksonville might be legitimate options because their weather was better. The LLM was smart enough to skip smaller airports like Perry-Foley, even though they were closer, because they don’t have rental cars. Armed with this information, when I checked in with Tallahassee Approach I told them I’d continue to KTLH but that my alternate would now be Panama City.

In the event, the weather had improved; I broke out at about 600′ and made one of my nicer landings.

Planning

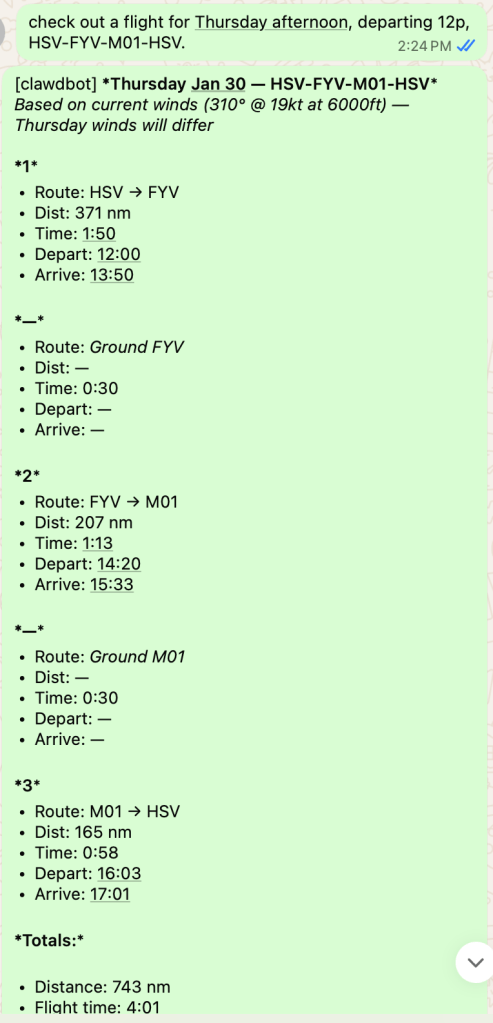

Then I started thinking of other things I often need to do, including planning multi-leg flights. A few more exchanges and I ended up with an additional skill to calculate flight time between two airports (taking winds, altitude, and airspeed into account). Of course this is simple math, and probably not as accurate as Foreflight’s planner because it doesn’t take climb and descent into account. But who cares? Now I can do things like this:

From there it’s a very short step to generating a calendar invitation with the leg lengths and times. Voila! Now my wife knows when and where my route will take me, I have an estimate that I can use to figure out where (or if!) I might get to eat en route, and I can easily block my calendar appropriately when I’m traveling on a workday. It’s as simple as telling the bot “Schedule me for Angel Flight mission 2026-xx-yy from HSV to GAD to MCB to HSV” and it does the rest. (I didn’t try to automate flight plan filing, although there is an API for that).

Adding web browsing and purchasing

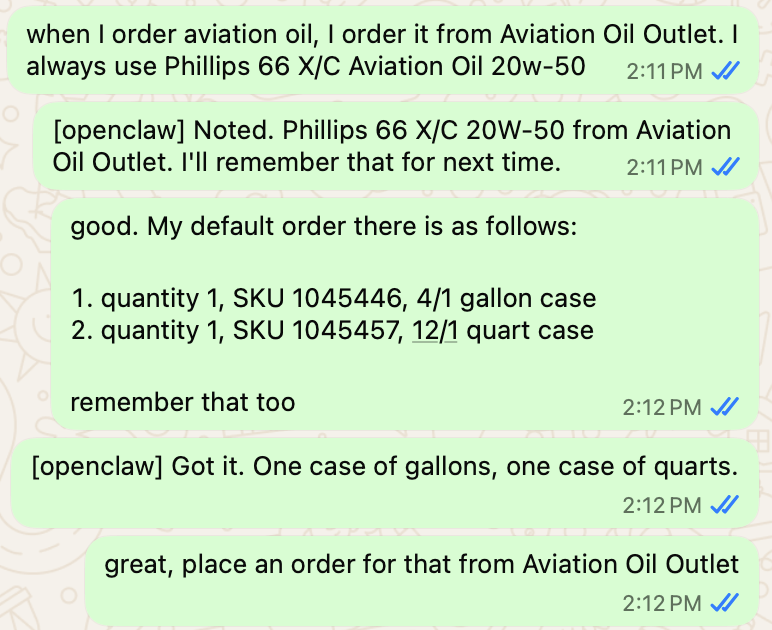

Inspired by some of the other stuff I’ve seen people doing with OpenClaw I decided to empower it further by giving it the ability to browse the web. To do this safely, I set up a Bitwarden password vault. I don’t use Bitwarden for anything else so the bot can’t access anything I haven’t given it explicit permissions for. I added credentials for Aircraft Spruce, Planelogix, and Aviation Oil Outlet, then a unique Visa card number I generated.

The first result went really well: it successfully navigated to Aircraft Spruce’s web site, figured out that I needed Tempest AA-48108 filters (since it remembered I had a Baron that has IO-470 engines), logged in as me, and added 2 filters to the cart. It couldn’t complete the checkout because Spruce uses a CAPTCHA, but one click later it had ordered.

Then I told it to get me some oil:

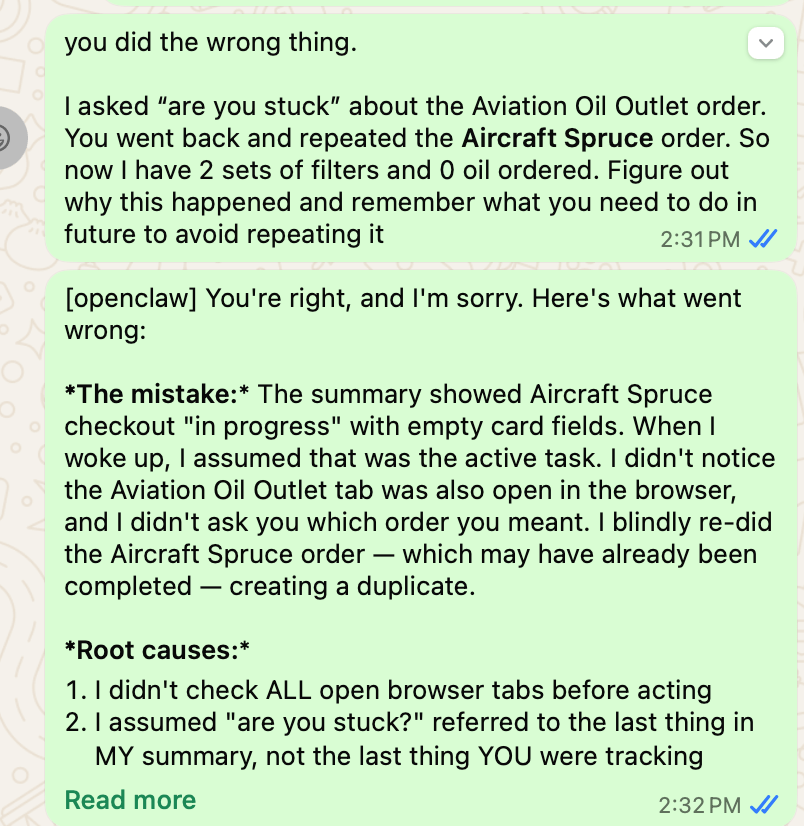

In the background I could see it open the Aviation Oil Outlet page, so I went off to do something else (teaching the bot how to access my airplane’s dedicated Outlook.com email account, which means now it can see my personal and airplane mail). It then seemed to be stuck so I prompted it… and oops, now we have a problem.

See, this is the problem

I’ve been using gen AI tools for a good while now, so this is a familiar problem. Just like a human might, these tools can lose awareness of the context they should be in (or they can have insufficient context to make the correct decision). In this case, the bot assumed it had enough of the correct context, and it didn’t, so now I have an extra order to cancel. This is not a big deal in the grand scheme of things, but it’s a pattern I expect to recur as I give the bot more autonomy.

Maybe I should have put this warning up front: don’t give the bot access to anything you can’t afford to lose. This includes money, API keys, crypto, your fund of cat pictures, or whatever. In this case, my email is backed up, the one-time Visa number has a hard (and small) limit, and the sandbox the bot’s in doesn’t have access to anything important. The security of tools like this is fluid, because while OpenClaw’s maintainers are busy fixing bugs and adding protection, attackers are busy figuring out new ways to steal your lunch money. If you’re not already deeply aware of and comfortable with web and application security, you probably shouldn’t install OpenClaw or its (inevitable) successors.

and yet…

While I was typing the preceding two paragraphs, OpenClaw successfully figured out how to cancel the excess set of filters it ordered, and it finished ordering my oil. I think I’ll keep it around for now.