A couple of weeks ago, I had my first real in-flight engine shutdown, with a bonus declared emergency as a cherry on top. I wanted to write up what happened and what I learned from it. I have about 1300 hours of total flight time, about 200 of which is in this airplane, so I am experienced enough to know that I can always learn and do better. I posted the below account on BeechTalk, and am also sharing it here, in the spirit of learning from the experience, both for me and possibly for others.

The planned flight was from Huntsville (KHSV) to Newnan County (KCCO, about a 40-minute drive south of Atlanta-Hartsfield). That’s about 50 minutes of flying time. I wanted to drop the plane off at Oasis Aviation for an autopilot repair. Weather was excellent– clear, sunny, and light winds– but I filed an IFR flight plan anyway, mostly so I’d have ATC support in case I needed it. My friend and former airplane partner was going to pick me up there and fly me back home.

I took from KHSV normally, with the usual weird Huntsville-to-Atlanta routing (a radial off GAD, followed by another radial off RMG, thence direct), and climbed to my planned altitude of 5000′. I eventually got cleared direct KCCO, and everything was awesome until it wasn’t.

About 20min into the flight, I noticed a slight but persistent shaking from the left engine. I didn’t like it because it was new. Checking the engine monitor showed me that the cylinder head temperatures (CHT) on cylinders 4 and 6 was significantly lower than normal, which I also didn’t like. The CHT reflects how hot the engine is running; when the fuel/air mixture is properly set, my CHTs run anywhere from 280ºF to 340ºF, depending on the outside temperature.

I tried adjusting the fuel mixture, which didn’t make the vibration any better or worse, and I tried switching magnetos, which also did nothing. Each engine has a pair of magnetos, and each cylinder has two spark plugs, so switching magnetos to see if the temperature of any cylinder or exhaust changes can be a useful diagnostic tool for things like broken spark plugs, bad wiring connections on the plug wires, and so on.

I flew along for a few more minutes and then the exhaust gas temperature (EGT) on cylinder 6 started dropping significantly too, to the point where the engine monitor was squawking about the difference in EGT between the highest and lowest temperature. That told me that something more serious might be wrong.

At that point, my mind was made up: grab the checklist, flip to the “abnormal procedures” page, and run the “engine shutdown in flight” checklist. That much was a total non-event. The checklist itself is simple: you cut off the supply of fuel to the engine by retarding the mixture control, shut off the engine fuel valve, feather the propeller (so that it turns sideways, thus reducing drag), and turn off the magnetos.

With the left engine shut down, I slowed up to about 135kts and lost a couple of hundred feet, which I was able to gain back. I called Atlanta Center and told them I’d lost an engine. For some reason, they were having great difficulty hearing me and they got another plane to relay communications back and forth until I had time to switch radios, after which they heard me OK. They gave me a block altitude of 4000-5000′, which was handy.

Learning point #1: Because I was headed adjacent to the ATL class B, and didn’t do it on my own, ATC declared an emergency for me. I could have done so myself, but, as God is my witness, I didn’t feel like it was an actual emergency at that point– it was just an inconvenience. The other engine was running fine; the weather was good; there were other airports within easy distance. There’s a lot of misunderstanding about what happens when you declare an emergency to ATC, but, in brief, it gives the controller latitude to move other airplanes out of your way and give you whatever services you need to ensure the best possible outcome. I didn’t think I needed any of that, so I didn’t ask for it.

Many pilots, not including me, are worried that if they declare, the FAA will get all in their grills. More on that later.

In retrospect, what I should have done is declared earlier. (Cue the scene where Maverick’s getting chewed out in Top Gun: “WHAT YOU SHOULD HAVE DONE IS LAND THAT PLANE.”)

At first I planned to continue on to Newnan. I knew they have maintenance on the field, and it was only about another 20 minutes. I flew on for another 5 minutes or so, then the thought dawned on me: how stupid would I look explaining my decision to the NTSB after an incident? I noticed that West Georgia Regional Airport (KCTJ) was pretty much directly in front of me. So learning point #2: my first reaction should have been to head for the nearest airport instead of even considering continuing the flight. Yes, it was only another 20 minutes, but still.

As I was heading towards KCTJ, I decided to try restarting the engine. It started easily but was showing the same symptoms, so I shut it right back down again. This is learning point #3: I had no reason other than blind optimism to think that whatever was wrong had magically fixed itself. I wouldn’t have tried a restart if there had been any indications of problems with fuel or lubrication. In retrospect, I should’ve just left it shut down since the rule I was taught was always not to restart an engine unless you know, and have corrected, what was wrong with it.

Throughout, ATC was super helpful. I didn’t need vectors to the airport because I could see it clearly, and I was already aligned with the one runway there. In fact, because I was darn near on top of the approach end of 17 at KCTJ, I had to fly a teardrop pattern to slow down and lose some altitude. I made a rather good one-engine landing (which is a little more challenging than it sounds) and taxied to the ramp.

After landing, I secured the plane, went inside, and opened an AOG (“aircraft on ground”) ticket with Savvy.

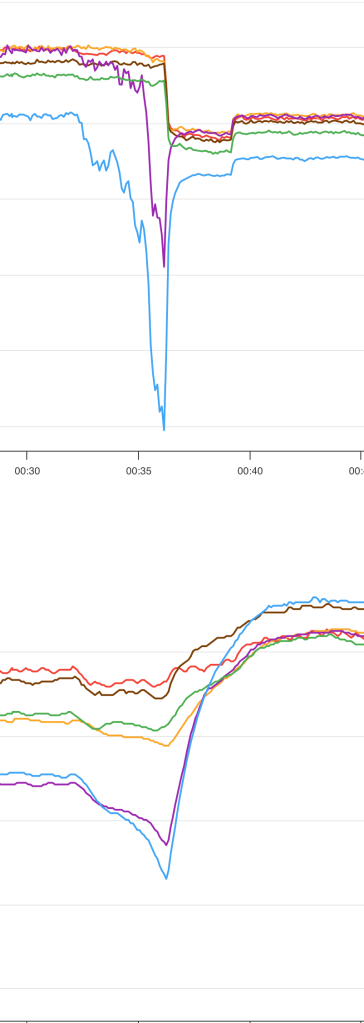

Here’s what the engine data looked like. The EGTs are shown in the top graph, and the CHTs on the bottom. The big dip in the EGT cyan line just after 35min marks the shutdown; before that you can see the discrepancy in CHT (the purple and cyan lines on the bottom graph) and EGT.

Savvy quarterbacked having the on-field shop take a look at the engine. There were several possible causes for the symptoms I saw, but the most likely was something that blocked the flow of fuel to the cylinders. If you don’t put enough fuel in, the cylinder won’t generate as much power, or get as hot, as its peers. This leads to vibration and suspicious temperature readings. Other possible causes included a stuck exhaust valve (where exhaust leaks out when it’s not supposed to, reducing the cylinder’s ability to make power) or damage to the camshaft or pushrods that operate the valves. The shop cleaned the fuel injectors and did a visual inspection using a borescope to verify that the cylinders and valves were OK. I flew the plane on to Newnan and it worked flawlessly.

Then last week, I got a call from an aviation safety inspector at the FAA. Remember, I mentioned that FAA action is a common worry that leads pilots of small planes not to declare an emergency when they need to. The ASI was courteous and asked me for a short statement of what happened and a log entry from the shop that implemented the fix. I sent it to him and that was that.

Pingback: 2023 year in review: flying | Paul's Down-Home Page