tl;dr: Starlink is an amazing addition to my airplane that makes my flying safer.

Last year, I bought a Starlink Mini antenna with the intention of using it in the plane. For $50/month, it sounded too good to be true… and it was, since Starlink nerfed the service after about a month by reducing its speed limit to 100mph. Over that speed, you’d get a petulant message telling you to slow down. The least expensive plan that would work at Baron speed was $250/month, and it wasn’t worth it to me.

The good news is that Starlink was apparently paying attention to the GA community and introduced a new “local priority” plan. For $45/month, you can use Starlink in motion, over land, at speeds of up to 250mph. You buy data in blocks of 50GB, for $20 each, so $65/month gets you up to 50GB of in-motion data. That’s about perfect for what I wanted.

The Starlink Mini hardware draws between 20 and 40 watts in normal operation, with a draw of up to 60W at startup. I have a 28V airplane, so I bought a 100W-capable USB-C PD cigarette-lighter plug and I was in business. I’m still working on a mounting solution that I really like; I’ll post more about that another time. Here’s a teaser picture of one attempt that didn’t work very well.

I wrote an article that should appear in next month’s Aviation Consumer that talks about how the system works in more detail. Instead I wanted this post to reflect on two recent flights where having Starlink in the plane made a measurable difference.

Before I get to that, let me briefly digress about in-flight weather data. The FAA operates a system called ADS-B. Part of that system is a subsystem called FIS-B that rebroadcasts weather data from the ground to airborne aircraft. This includes both information about current conditions, but also forecasted warnings. The most important thing to know about this data is that it is not guaranteed to be in real time. There is typically a delay of between 5 and 20 minutes for radar updates. The data comes from the National Weather Service network of WSR-88D radar systems and then is processed in various ways. That processing takes a while. And so what you see in FIS-B is what things looked like at the time that radar image was taken. As famous aviation writer Richard Collins was known to say, “The only weather report you can trust is what you see out the window.” Many pilots have come to grief by trying to use this time-delayed radar image to navigate around storms and instead ending up in the storm area.

I don’t have onboard radar, but I do have onboard lightning detection. The combination of the FIS-B radar data, the onboard lightning detection, and my eyeball usually works pretty well to help me make tactical decisions. But eyeballs and sferics don’t do any good for long-distance planning. FIS-B has a lower-resolution radar feed that includes the entire continental US, but that’s also time-delayed. My electronic flight bag (EFB) app, ForeFlight, has higher-resolution radar layers available via the Internet, but that doesn’t help in flight… until now.

The first case was when I was flying back from Dallas for work. There were storms forecast for western Mississippi and northwestern Alabama, and it looked like I would, just maybe, beat them home. I wanted to have a plan in place in case I didn’t, though.

Enter Starlink. Here’s a sample screen shot from the RadarScope app, showing minimally-processed output from the WSR-88D at Hytop. This data is still not quite real time, but it’s much higher resolution than the FIS-B feed. RadarScope lets me see additional radar data types, not just reflectivity, so it’s much easier to figure out whether the radar returns actually represent a growing storm, a more benign area of rain, or a dangerous full-grown embedded thunderstorm cell. I pulled up RadarScope and was able to look at the radars across AL, MS, and TN to get an idea of what the storm line was doing. Then I swapped over to watch a Facebook Live broadcast by local meteorologist Brad Travis. He was predicting the storm arrival time, severity, and impact across the area west of Huntsville, exactly where I was going to be flying. The combination of updated radar data and a real-time review of that data by an expert told me it was time to land and wait the storm out. I diverted to the airport at Haleyville, waited about an hour in dry safety while the storm blew through, and had an uneventful return to Huntsville.

The second case was on a recent trip to visit my mom and sister in Galveston. The weather at Galveston had been gusty and cloudy thanks to two large low-pressure systems with a high trapped in between them. Here’s a comparison of what I saw from FIS-B versus what I saw in Foreflight radar data. First the ForeFlight image: there’s a storm cell to the upper-right of my flight path (past KBMT), and another off to the left, but no serious precipitation, and no storms, along my route of flight.

On the way home, I had the same problem; those two low-pressure areas were boiling up a 400-mile-long line of storms to my north. I planned to leave Galveston southbound and then turn east to fly along the lower edge of the Louisiana coast. Unfortunately, the weather at Lake Charles, and to the north, was terrible, so I ended up getting routed to Grand Isle. Here’s ForeFlight, showing the FIS-B data. You can see how much lightning there is in and around the straight-line path from Galveston to Huntsville.

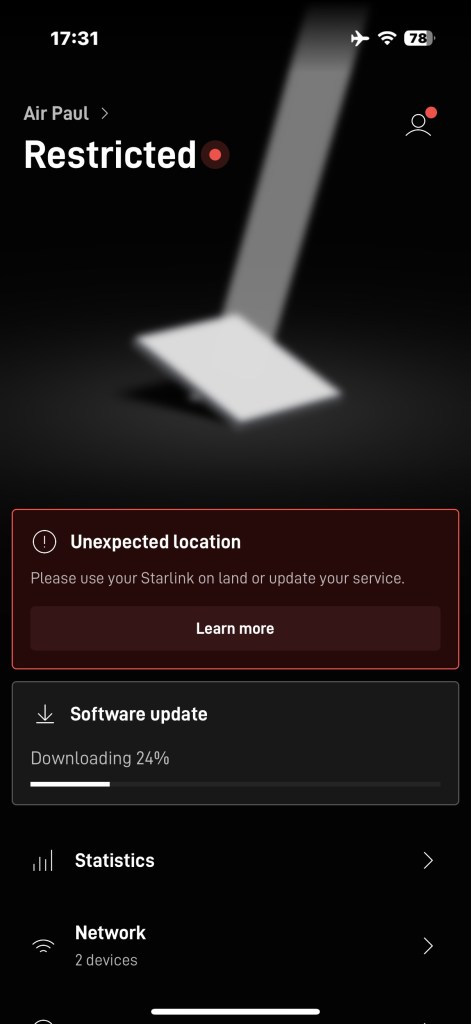

You might wonder why this image shows the FIS-B data. It turns out that the local priority plan for Starlink only works over land and in coastal waters and I was about 40 miles offshore, well outside the 12-mile coastal-water limit. I didn’t get service back until I was nearly to Grand Isle. In fairness, FIS-B is only available in CONUS too; for example, if you fly to Canada or the Bahamas, you won’t have FIS-B weather data.

There were a number of pop-up thunderstorms along my route; the easy availability of updated and timely radar data helped me proactively ask for route changes to stay well away from them.

I’m not even touching on the utility of being able to use the Internet in cruise flight. Running behind schedule? Call the FBO and tell them. Diverting for weather? Book a hotel at your new destination. Bored passengers? Let them watch Netflix. All of the same capabilities that make in-flight Internet so useful on commercial flights apply here too, but to me, the safety benefits of getting better-quality weather data, and more of it, and in less time, make Starlink a must-have.

Pingback: 2025 year in review: flying | Paul's Down-Home Page